Songs, scents and souvenirs: maximising music revenues

Today’s universe of alternative investments is beginning to embrace royalties from music and software patents, but management of funds can prove an issue in this intriguing asset class.

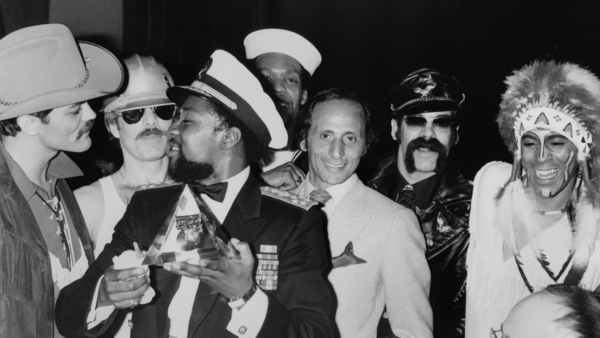

Growing up watching his father Henri produce a colourful band who dressed up as cowboys, Red Indians and construction workers as part of popular music sensation, the Village People, Jonathan Belolo felt he was living in a playground.

By the time he was entering his teens, the games were turning into work. “My father would do all the royalties himself manually, with a pen, paper and calculator, clearing the living room and spreading all the files over the table for two or three days,” he recalls fondly.

From the age of 12, he got to know “artists, writers and everybody else” working for his father’s record label, Scorpio Music, and by his early 20s, Jonathan was helping stage concerts for global stars such as soul singer James Brown.

A short stint at investment bank Morgan Stanley where “they taught me to use Excel and analyse Bloomberg,” further fuelled his interest in the financial side of the music business and his appetite to invest in high-tech innovations.

Now the younger Mr Belolo is using this experience to revive the Village People’s brand, planning a documentary about the band’s early days in the 1970s, as style icons inspiring Manhattan’s gay community, spent in the clubs of Greenwich Village.

Maximising revenues from music can include putting on shows, producing documentaries and selling branded goods

He and his brother Anthony have signed a deal with New York-based investment firm Primary Wave Music, to help attract funds and maximise revenue from the band’s back catalogue, which boasts more than 100 million records sold worldwide.

Primary Wave plans to do for the Village People what it has already achieved for other artists, including The Ramones, Kool & The Gang and Isaac Hayes. Their investment strategy involves spinning off as many profit lines as possible, in addition to leveraging music royalties. “We created a Waterford Crystal line for Luther Vandross,” recounts Larry Mestel, founder and CEO of Primary Wave. He also brewed a beer called ‘Oh Mama’, taken from the lyrics of Renegade, a big hit by the Chicago-based rock band Styx.

Mr Mestel knew Henri Belolo during the days of the Studio 54 Club in New York, although the two never worked together. Now, in addition to the documentary, the schedule will likely include a video game and a Broadway Show. The latter presents a challenging economic model, with a major production costing $750,000 per week to stage and few projects making any real return.

Dynamic investment strategy

One of the reasons for unprofitable franchises, says industry veteran Mr Mestel, is lack of dynamic investment strategy. “The risk comes if you just buy and hold, and the income stream stays flat or begins to deteriorate,” he suggests. “If you're buying these types of assets, you really need to have a strategy to market and increase value. That's why we buy the name, likeness, image and life rights, which gives us ability to do things that others cannot.”

The music industry as an asset class is in its early stage, he believes. “I’ve been doing this for 18 years and we’ve never had more success. This is a fantastic business for people to be in from an investment perspective,” he says, highlighting a $2bn investment in his firm by $900bn alternatives specialist Brookfield Asset Management, which became a strategic partner in 2022.

His proudest moments came in working with the estate of soul diva Whitney Houston. This started with a biographical film, a worldwide cosmetic line and a perfume brand sold in Walmart. But it took some deep delving into the deceased singer’s recording library to really hit the jackpot.

“When we partnered with Whitney’s estate, we went into the vault and found some unreleased material, from when she covered Steve Winwood’s ‘Higher Love’ in 1990,” he says, recounting how the track was then remixed for a more contemporary feel.

“We walked into RCA Records and, six or seven weeks later, we had a number-one hit in eight different countries,” he remembers proudly, recalling a time when the narrative about Ms Houston’s life had turned very negative. “All those years after her passing, she became once more the greatest voice of her generation, with brand opportunities and increased streams. That song was streamed 900 million times and it totally re-shaped the conversation around Whitney.”

But not all music royalty arrangements have run so smoothly, with the bumpy ride offered by the Hipgnosis Songs fund — whose catalogue includes numbers from Blondie and Neil Young — being a case in point. Amid tensions between the fund’s board and its investment adviser, the Guernsey-based vehicle was forced to reduce its portfolio valuation following US rulings about the level of royalties which artists were entitled to. Investors had also voted down a deal to sell a $440m music rights portfolio to another fund managed by Blackstone, the private equity giant.

Musical innovators

Hipgnosis was established in 2018 by Merck Mercuriadis, who had managed recording stars including Beyoncé. Nile Rodgers, bandleader of disco pioneers Chic — who sang about Studio 54 in their 1978 dancefloor classic ‘Le Freak’ — and a musical innovator known for mingling with private bankers, was also a co-founder.

“You should only invest in things you know about,” warns one music industry player. Another insider says: “Hipgnosis was never an investment, asset class or an industry issue. It was more of a manager issue.”

Those close to the fund point to more specific factors. “There was a major problem with the deals they did and the prices they paid,” says Simon Lapthorne, London-based senior research analyst for Investec Wealth & Investment, the largest single shareholder in the Hipgnosis fund. “But they bought, on the whole, pretty high-quality assets. And no two of these things — assets or catalogues — are alike.”

He also points to “a perceived conflict of interest in in the relationship with Blackstone and the terms on which they were proposing to sell some assets to Blackstone,” and a decline in royalties for more recent tunes, which did not match higher prices commanded by some classic, vintage numbers.

In future, publicly quoted record labels such as Warner Music Group or Universal Music Group might be preferred by investors, because they also have significant musical publishing activities, Mr Lapthorne adds.

Software licensing

He also believes investors can receive a similar income return profile from software licensing, which closely resembles the music industry model. “The software industry moved some years ago from a perpetual, on-premise licence of picking up a laptop at PC World and installing Microsoft office on it, to a subscription-led, cloud-based model that offers much higher quality and magnitude of earnings.” He mentions Adobe and Microsoft as two key stocks that benefit from this earnings model.

The music industry, he says, has gone down a similar route. “Instead of pitching up at HMV and buying a new CD every few months, we shell out ten pounds a month to Spotify to access all the music in the world. We enjoy a much better experience and it’s a much better model for the music industry,” says Mr Lapthorne.

The handful of asset managers that promote so-called intangible assets by investing in music royalties and software patents see them very much as fitting in the ‘alternatives’ bucket held by pension funds and family offices.

“If you look 10 years ahead, most alternative asset managers will invest in intangible assets,” says Christian Czernich, founder and CEO of Vienna-based Round2Capital. “If you [compare] the volume of private equity that is invested in software companies [today with the volume we had five years ago], you will see a very strong increase. A lot of private equity firms that historically have not been investing in software companies, for instance, are now massively allocating to the sector.”

If you look 10 years ahead, most alternative asset managers will invest in intangible assets

The idea to launch a fund focused on these assets came to Mr Czernich two decades ago when researching his PhD on patterns in multinational organisations at the Stockholm School of Economics. “It was clear the value of their businesses was built on intangible assets, their know-how on patents and ability to innovate,” he says, adding that ten per cent of spending in the pharmaceutical industry is also done via royalty investments. “It was never about the efficiency of their production facilities.”

Knowledge transfer

The next stage, he believes, will be transfer of skills from “the small market” of music royalty funds and pharmaceuticals to a potentially much larger asset base encompassing software investments. “This innovation will come from sectors where royalty financing is already established and people are looking for new applications of those instruments,” says Mr Czernich.

For many family offices associated with musical dynasties, however, these investments are often as much about building the family legacy as they are about generating returns for the portfolio.

Clearly some of the publicity that the legacy of the Village People has received has not always been in the spirit of the original project, with its roots in the vibrant LGBT culture of 1970s New York.

Against Mr Belolo’s wishes, and those of the relatives of other surviving band members, the best-selling tracks YMCA and Go West were used by Donald Trump’s campaign in his failed 2020 Presidential re-election bid.

For many musical dynasties, building a family legacy can be just as important as generating financial returns

“Trump’s right wing vision was about young Christian Americans visiting the YMCA,” laughs Mr Belolo. “That’s very, very different from what activists in San Francisco see when they look at the videos.” His hope is that in terms of both returns and legacy, the ghosts of the cowboy, the Red Indian and the construction worker will be having the last laugh.