Global and regional wealth managers are facing off in Singapore and Hong Kong as the battle for the custom of Asian tycoons gathers momentum

Over breakfast of avocado on sourdough toast at Singapore’s 67 Pall Mall club, Silvio Struebi, head of Asia Pacific banking at consultancy Simon-Kucher & Partners, talks about the region’s wealth managers and how they are expanding their menu.

Most families bringing business to Singapore from other Asian economies seek operational efficiency, centralised accounting and residency advantages, ahead of investment expertise, he says.

“For a lot of Asian family offices, succession planning is not yet on the horizon,” says Mr Struebi, who worked with wealth and asset managers in Switzerland, before relocating to Singapore 15 years ago.

Since Covid, attitudes to risk have begun to change. “With war, instability and high interest rates, many families feel like we are going back to the 1970s,” he says. “The younger generation is not used to this. Until recently, they thought life was like Instagram.”

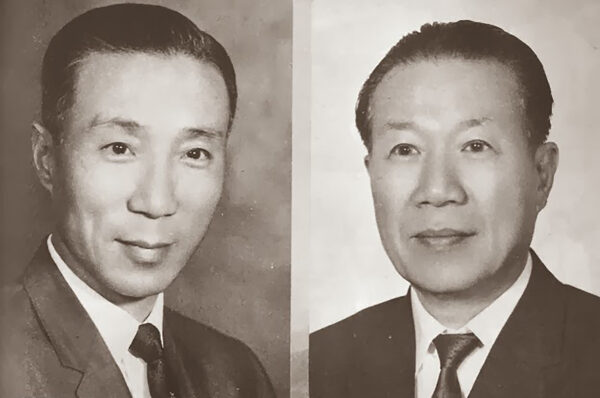

How the industry will bring together various generations to respond to these risks will prove a major challenge. From this penthouse club in Singapore’s Shaw Centre — built by legendary brothers Run Run and Runme Shaw, who migrated from Qing dynasty, mainland China in the early 20 century — Mr Struebi points out the property developments which transformed Singapore over the past two decades.

“All the families here want to talk about real estate and private equity deals, not discretionary portfolios,” he says. “They want to be part of this amazing growth story.”

Next generation transfer

When the Shaw brothers began transferring assets to the next generation, it proved far from straightforward. Not only did their organisation boast operations in Hong Kong, mainland China and much of Southeast Asia, where their film business thrived, but like with similar dynasties, there was no obvious successor to the long-term patriarchs.

Many other transfers of wealth have also made the news. A dispute over $1.45bn in assets split between the 13 children of Hong Kong property tycoon Henry Fok was only settled in 2022, 16 years after his death.

The $10.6bn estate of the late Stanley Ho, a Macau magnate who controlled much of the city’s casino industry, proved challenging to negotiate, with a sprawling cast of family characters, including 17 children he fathered with four different partners.

Most advisers dealing with these extended families work within the big banks in Singapore’s burgeoning wealth management industry — the likes of DBS, HSBC and Standard Chartered. These banks are based in the towers of the Marina Bay Financial Centre, linked by pedestrian tunnels to more traditional parts of the city, housing the Fullerton Hotel and the Lau Pa Sat emporium of food stalls.

These banks have benefited from an exodus of advisers from Hong Kong, many of whom brought wealthy clients with them. “We talk to most of the big families in Asia and I think Covid changed everything,” says Joseph Poon, head of DBS Private Bank. “The next generation are now looking for meaning and impact in the world, rather than strictly following what their parents want them to do.”

Family governance in focus

Some in the older generation entered a “state of panic,” as their offspring refused to dutifully enter the family business. “That expectation is now gone,” admits Mr Poon. “Their children are doing things more impactful, whether it’s technology, a start-up or something more purposeful.”

This is why the role of banks is expanding to provide a family governance structure, bringing generations together to oversee both businesses and investments.

“This involves a family business and corporate relationship, not just financial work,” says Mr Poon. Although the children may not be involved in the business, they are still keen to maintain its value. “So, this becomes an integrated conversation with us about not just financial wealth succession, but also the business succession,” he adds.

The manifestation of such a cross-generational, family discussion is “quite a new thing” and has become “much more pronounced since Covid”, when families under lockdown, previously embarrassed by Asian cultural reluctance to discuss death, were finally forced by proximity to ponder mortality and their collective future.

At HSBC, on the 50th floor of Tower 2, advisers are on alert to roll out red carpet treatment for clients visiting from mainland China, Indonesia and increasingly India. Transfer of assets to the next generation is fast becoming a priority.

A regular visitor to the towers is Annabel Spring, CEO of HSBC Global Private Banking and Wealth, who speaks about “the emotional difficulty of talking about our own mortality,” which means discussions about succession planning, particularly in Asia, are often left for another day.

Younger generations, she finds, are often keen to take on more responsibility in the family business or wealth, but lack the knowledge, experience or confidence to do so. In order to help them, banks put on specialist conferences — popularly known as ‘Next Gen boot camps’ — for younger branches of families.

These allow the youngsters, many in their 20s, to gain hands-on experience of how to run family businesses and philanthropic ventures. HSBC ran such an event in Dubai in January, focusing on family governance, where younger family members were persuaded to share experiences.

“We put a lot of focus on helping attendees meet like-minded peers, so they can build a support network in the years ahead,” says Ms Spring, pointing to key differences between this younger generation and their parents in investment preferences, with conversations now likely to cover value and purpose.

“The next generation are increasingly interested in embedding strong values in many aspects of their lives and business,” says Ms Spring, whose relationship managers are beginning to focus on environmental, social and governance policies, impact investments and how to shape a family’s philanthropy, in discussions with younger cohorts.

The way in which decisions are made also differs. “The younger generations are also keener to favour using technology in how they apply their decisions, and with fast-moving innovations like artificial intelligence changing how we do business, we are seeing a more entrepreneurial mentality,” she says.

Prioritising planning over products

But there are also many risks to successful succession planning identified by major banks and boutique wealth advisers. Because this is such a sensitive area, it is essential for banks to engage with clients empathetically, while providing objective advice. This is not always the case with big banks, which are often accused of encouraging advisers to prioritise product sales.

Succession planning risks, says Elizabeth Hart, founder of Legacy Wealth Advisors in Singapore, and former private banker with LGT and Rothschild Trust, include creditor claims, corporate disputes and divorce, in addition to investment risks.

“The biggest risk of all is family disputes,” says Ms Hart, who deals with mainland Chinese and Southeast Asian clients. “Family wellness is the missing piece. What is the point of having a great investment policy and structure, if there is no harmony in the family?”

French bank BNP Paribas has what it calls a “sales force” to populate investors’ portfolios, separated from a specialised team of wealth planners — much smaller in number — to focus on the succession piece.

“Our wealth planners have a whole different expertise,” says Arnaud Tellier, Asian regional head of BNP Paribas Wealth Management, based in Hong Kong after transferring from Singapore. “What they bring to the table is very different from traditional investments. They bring the softer side. You can’t really complete the circle without these relationships and without these plans.”

But there is a growing view in the industry that wealthy families are seeking leadership and ideas about how to arrange their wealth, which traditional banks can struggle to provide.

“A lot of Asian families are looking for good examples of what other families have done in navigating the usual disruptions to family business over time,” says Ping Ping Lim, head of Asia–Pacific global family wealth at LGT Private Banking Group.

She says many feel more comfortable dealing with her firm’s family owned business to help arrange their succession planning than a universal bank. “We can bring to you the knowledge and heritage of a family who has been able to successfully transfer wealth to the 26th generation today.”

The menu offered by wealth managers is expanding to include a variety of new plates involving succession planning. But there are two key questions remaining: can they cook up the correct recipes for an increasingly demanding client base? And do they have enough well-trained advisers to serve up the dishes?